Do Theatrical Films Really Massively Outperform Straight-To-Streaming Films?

A new look at the US viewership data of straight-to-streaming movies and theatrical films.

Why this new analysis?

In the debate of “streaming versus cinema,” one of the most recurring arguments is that “films released in theaters perform better in streaming than films that are released directly on streaming.” And the go-to analysis for this argument is a multi-part study by analyst The Entertainment Strategy Guy from 2023, which I have linked below.

If you can, I really suggest you give it a read because alongside my own analysis, it shows how the same data, when analyzed and cut in different ways, produce different outcomes.

It all boils down to the methodology you decide to follow and the one used in his analysis has, with all due respect to its author, some pretty big flaws. Firstly, the study relies solely on viewing hours without contextualizing them (for example, comparing the viewing hours of 2.5-hour films with those of 1.5-hour films on an equal footing). More importantly, it claims to use viewing data for the first four weeks of release to better compare titles (which is a perfectly valid way to go about this matter). However, upon closer inspection, it turns out that for most films, the study actually uses data for only one week, or even just a few days of viewing, since most of the films used in the analysis did not stay 4 consecutive weeks in the Nielsen Top 10.

These incomplete viewing figures then feed into the “four-week” averages that underpin the thesis but weigh more heavily on straight-to-streaming films. Those two methodological choices eventually lead to its conclusion that theatrical films do overperform on streaming.

That’s why I decided to try and be constructive and do my own analysis, based on the same numbers, updated with 2023 and half of 2024 numbers but with what I think is a better and more telling methodology. I understand this feels like an obscure niche battle of methodologies above all else but this is an important topic in the streaming world.

Methodology

Here is the methodology I used in this analysis. Please read it carefully as it is probably the most important part of the article.

The data I used comes from Nielsen’s weekly Top 10s that cover the TV viewings in the US only, from January 1st 2021 to July 31st 2024, since the start of Nielsen’s triple weekly charts (one for series, one for films and one for acquired content). The analysis only covers English-speaking films and some films may have been released before January 1st, 2021 such as Soul but not Wonder Woman 1984 for which we only have data for its first 3 days.

Nielsen shares its data in “minutes viewed” for a given week, from Monday to Sunday. I then divided those minutes viewed by the runtime of each film. This is a simple reverse-engineering of what Nielsen does, as explained by Brian Fuhrer, SVP at Nielsen in its Streaming Top 10 Explainer : “We take the average number of people that are viewing each minute of that program […] and we multiply that by the duration. That’s how we come up with minutes viewed.” So by dividing the numbers of minutes viewed shared by Nielsen by the runtime of each film, we fall back on the average number of people that watched it in its entirety, one metric that is similar to the Complete Viewing Equivalent that I use on a regular basis for my weekly Netflix and Nielsen ratings articles. That’s why I will call it CVEs throughout this study and it allows for a better comparison between programs of different duration.

To get the largest exploitable and apples-to-apples sample of films on most services, I decided to focus on the first 14 days after the release of each film, because it is enough to know if a film is a hit or not. This means that, unless stated otherwise, all the films used in this analysis managed to stay at least three consecutive weeks in Nielsen’s Top 10, which allows me to estimate a number of CVEs for 14 days. This methodology allows to study approximately 180 films, 115 straight-to-streaming films and 65 theatrical films.

There is one important thing to keep in mind when it comes to Nielsen’s data about theatrical films: Since it is based on audio trackers, Nielsen cannot distinguish viewings made on streaming services and viewings made on transactional services. It means that if a film available both on streaming or to rent is watched because it was rented, its viewing will be attributed to the streaming services on which it is available. Logically so, that tends to artificially inflate the numbers for theatrical films that are also available to rent or buy as part of the regular windowing of release post-theatrical, while it does not have any impact on straight-to-streaming films that are usually exclusive to a streaming service. It is a pretty huge caveat for Nielsen but that’s one with no definitive solution and hard to quantify.

I only kept in this analysis theatrical films that were released on streaming services during a Pay-1 or a Pay-2 window, not the catalog titles that come and go on a regular basis from streaming services.

Between 2021 and now, Nielsen added more streaming services to its weekly Top 10, adding notably Max, Peacock, Paramount+. Some theatrical or streaming original films released on those services before they were supported by Nielsen are then not included in this analysis because we just do not have any numbers for them and that’s too bad, both for some straight-to-streaming titles or theatrical ones.

A general overview

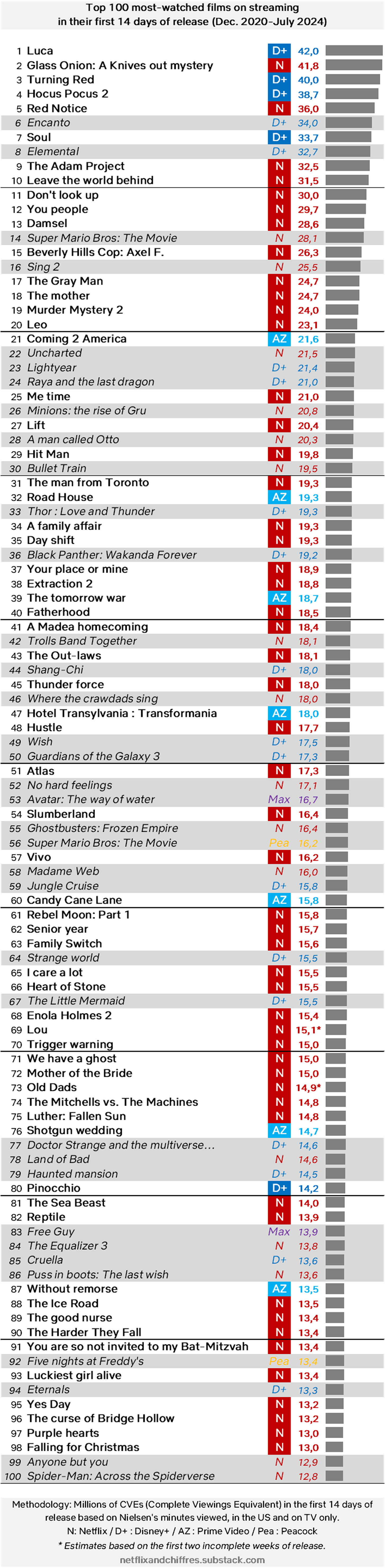

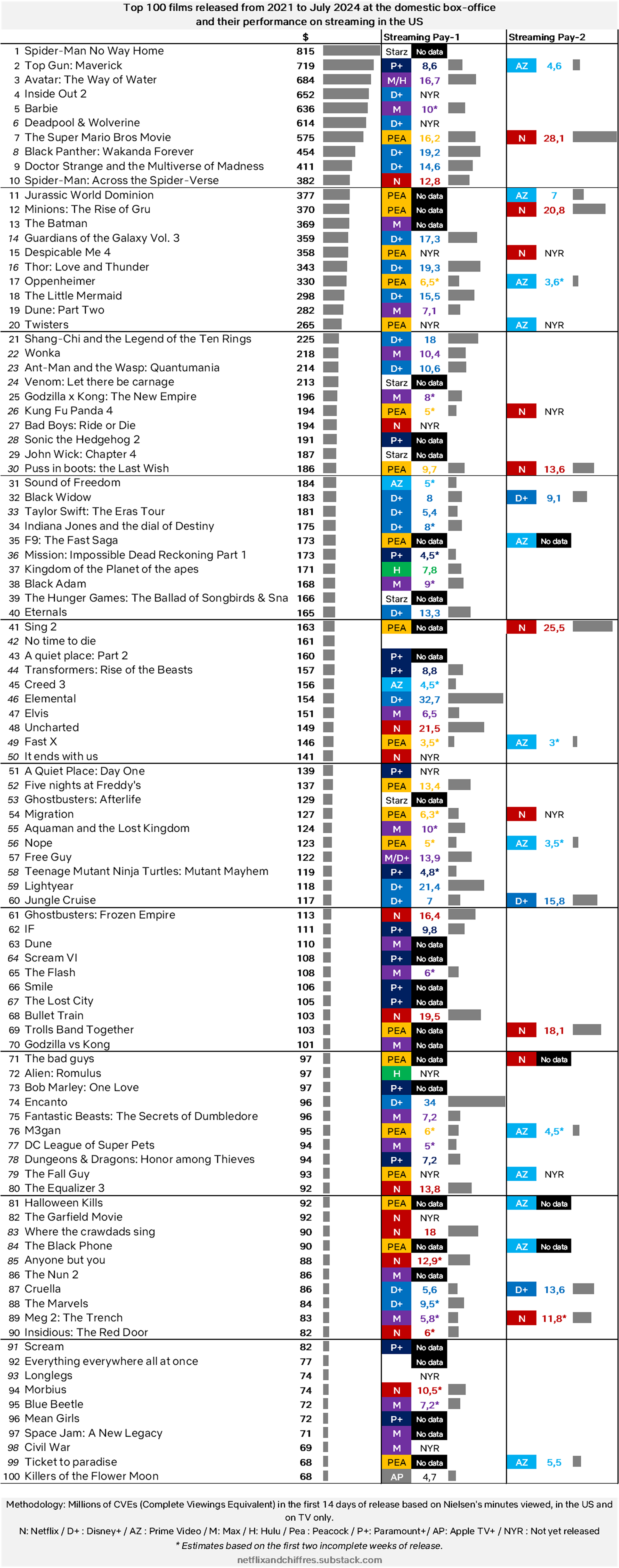

The first thing I did for this analysis is to establish the ranking of the 100 most-watched films on streaming during their first 14 days of availability released since 2021. This list has streaming original films of course and theatrical films released on streaming services during Pay-1 or Pay-2 windows.

Why only take into account films that performed well on streaming as a basis for this analysis? Well, first because with its Top 10, Nielsen only offers a glimpse into was can be considered as hits on streaming. Everything that falls beneath the surface of the Top 10 is invisible and so unusable in the context of this data-driven analysis. Furthermore, the question at hand is to ask if theatrical films overperform on streaming compared to straight-to-streaming films so it stands to reason to take a look at the “hits” (or films that managed to stick at least 3 weeks in the Top 10) on both sides, to see which ones were actually the most-watched.

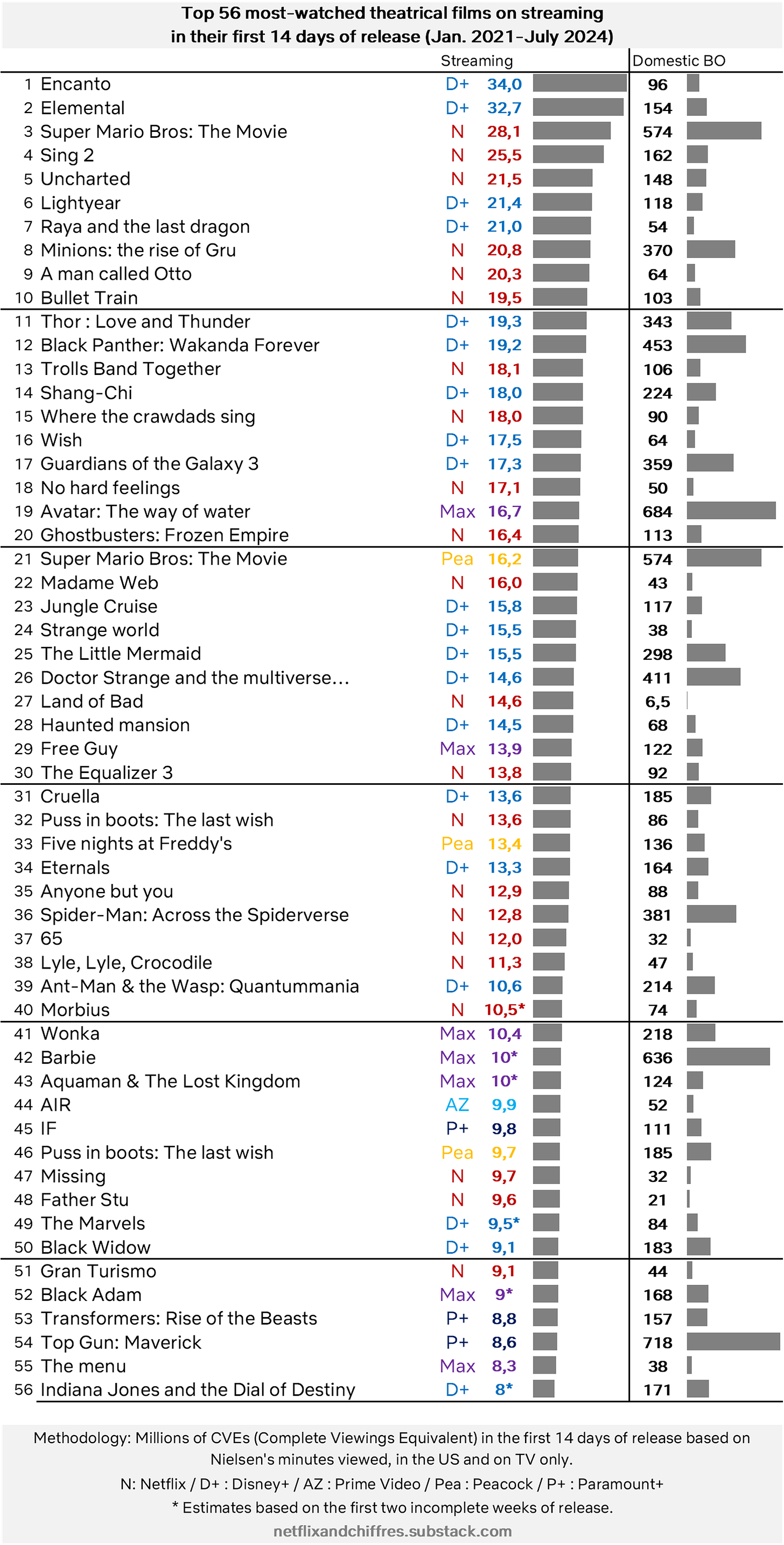

This ranking of the 100 most-watched films on streaming in their first 14 days of release on streaming services offers a pretty self-explanatory first overview on the topic. Theatrical films are displayed in grey.

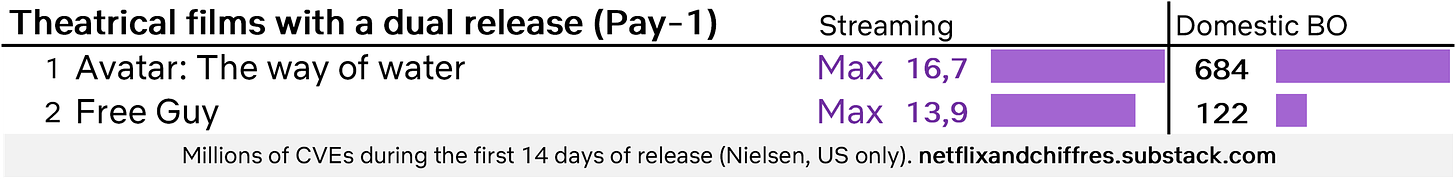

Out of this Top 100, 36 films were released before in theaters (35 even as The Super Mario Bros Movie is featured twice, for both its Pay windows on Peacock and then Netflix). There are also some peculiar cases, such as Five nights at Freddy’s (that was released in theaters and on Peacock day-and-date), Free Guy (that was released on Disney+ and Max on the same day), or Avatar: The Way of Water (that was released on Hulu and Max on the same day).

If we stick to this Top 100, which is already a pretty extensive look at 3 years and a half of streaming successes, 64% of the films are straight-to-streaming films and 36% are theatrical films. That could be enough to answer the question at hand but let’s try and dig deeper.

The first thing to notice is that out of the 36 theatrical films in this Top 100, 12 are animated movies and the first live action theatrical film of this top is #22 (Uncharted). Out of those 36 theatrical films, 24 are either adaptations or sequels of known IPs (with 7 for the Extended Marvel Cinematic Universe), leaving only 12% of this Top 100 for original theatrical films.

Among straight-to-streaming films, there are only 12 sequels and adaptations out of 64 films, which means that when original theatrical films only manage to get 12% of the Top 100, straight-to-streaming really original films make up 43% of the Top 100. That’s the first thing to learn from that chart : straight-to-streaming hits are more likely to be original films while theatrical films that are hits on streaming are more likely to be adaptations and sequels.

That is why Disney thrives among theatrical distributors in this Top 100, accounting for 18 films out of the 36, versus 6 for Universal and 10 for Sony. The only real anomaly here is Land of Bad which did very well on Netflix besides a very limited release and the fact that it’s not part of a big splashy output deal on Netflix.

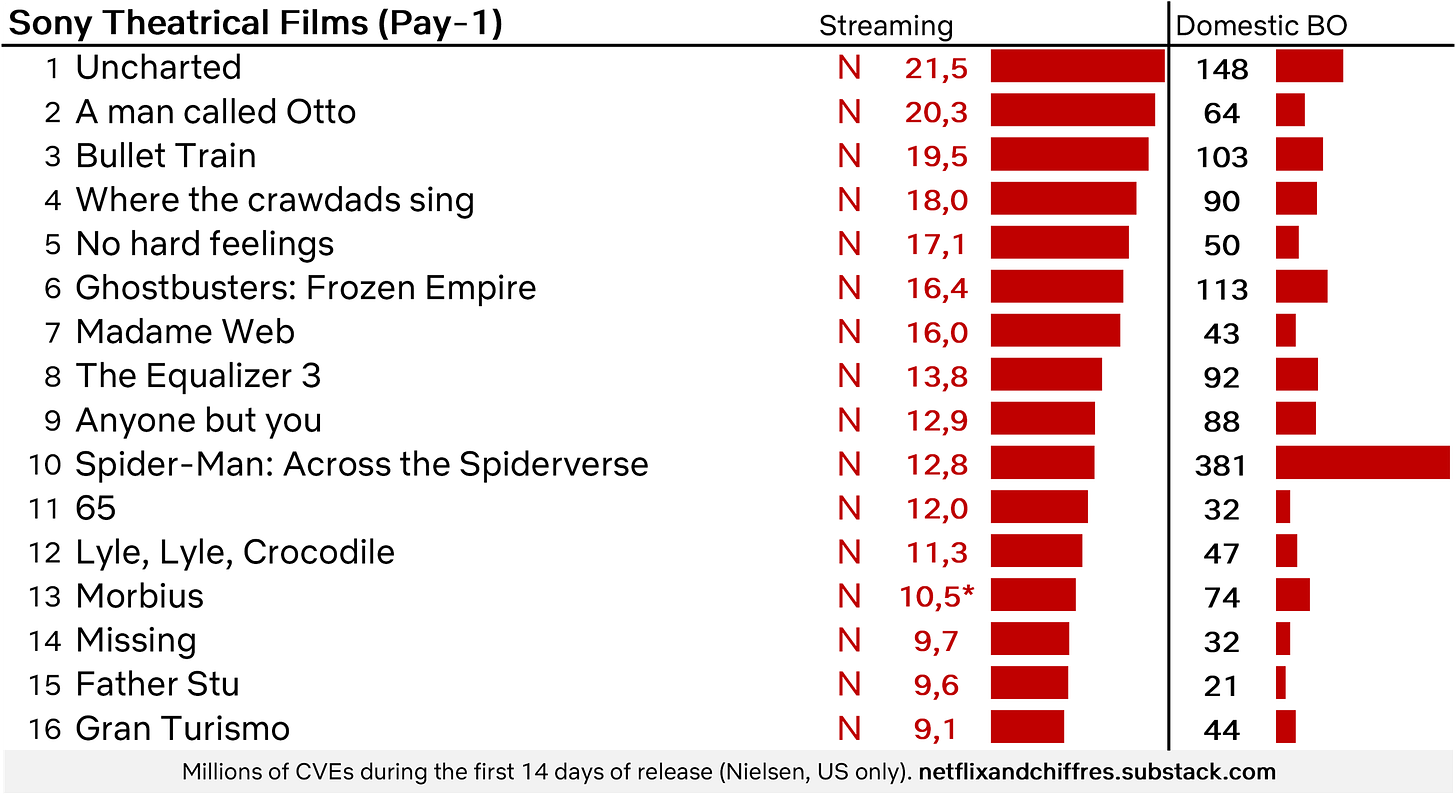

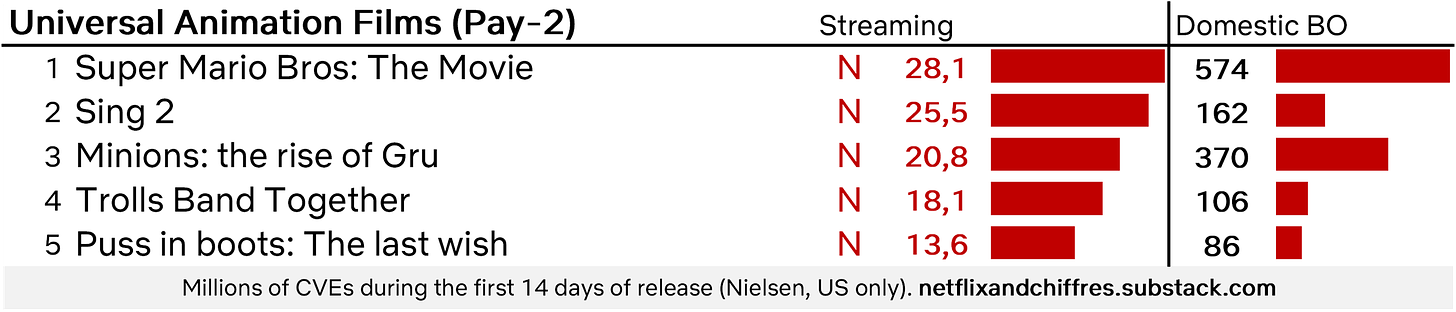

That’s a time as good as any to detail those output deals. Every theatrical Disney film goes to Disney+, which is logical. For their Fox films, Max used to be the output service until Avatar: The way of water before switching to Hulu. Universal has two output deals. For its live action films, the Pay-1 window goes to Peacock whilst the Pay-2 window goes to Prime Video. For its animated films however, the Pay-2 window goes to Netflix after a run on Peacock. Warner films go to Max and then can go anywhere for the Pay-2 window (recently, some of those films went to Netflix co-exclusively). Finally, Sony films have been going to Netflix for their Pay-1 window, explaining why so many Sony films appear in the Top 100.

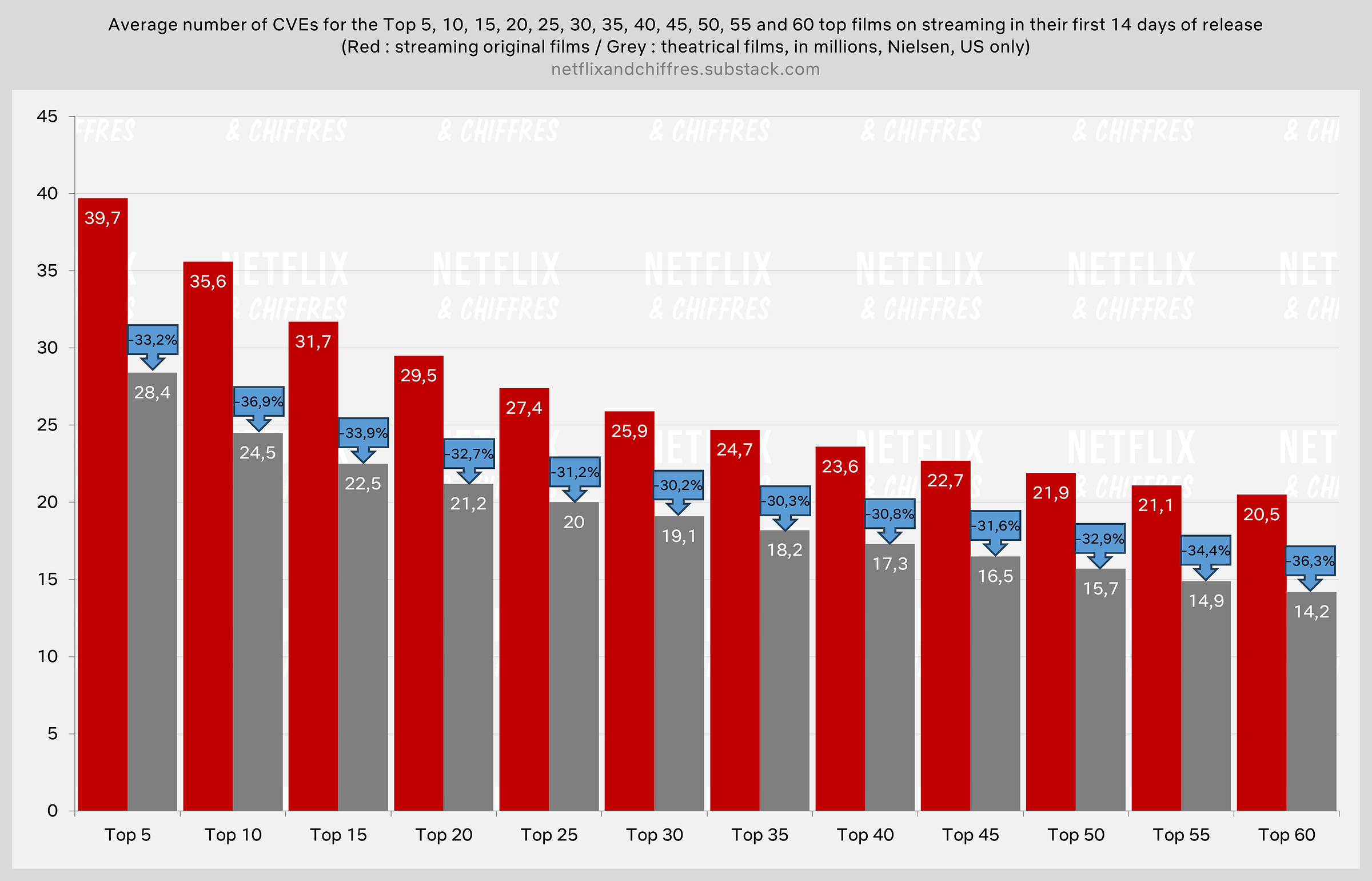

Starting from this Top 100, I then proceeded to calculate the averages of the Top 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55 and finally Top 60 of the most-watched straight-to-streaming films and of the most-watched theatrical films (I had to go deeper than the Top 100 to find the 60 most-watched theatrical films). Here are the results:

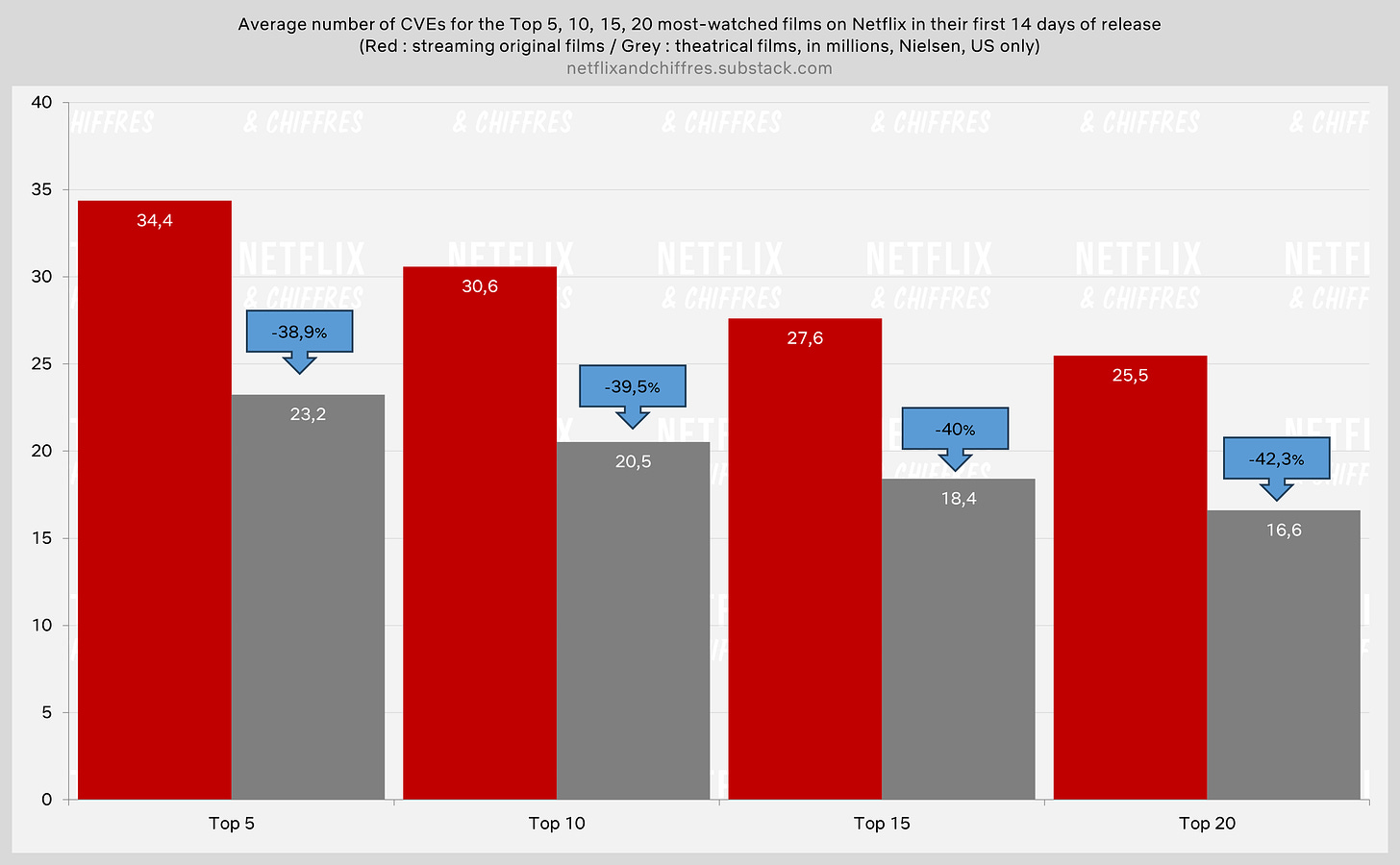

On average, the most-watched straight-to-streaming films are 30 to 37% more watched than the most-watched theatrical films during their first 14 days of release, with a gap widening more as we go down in the charts. And that’s without accounting for the fact that Nielsen tends to inflate the numbers for theatrical films that are available to rent or buy at the same time of their streaming release !

That’s the first hard data point to consider here but as we will see, every streaming service has its own peculiarities.

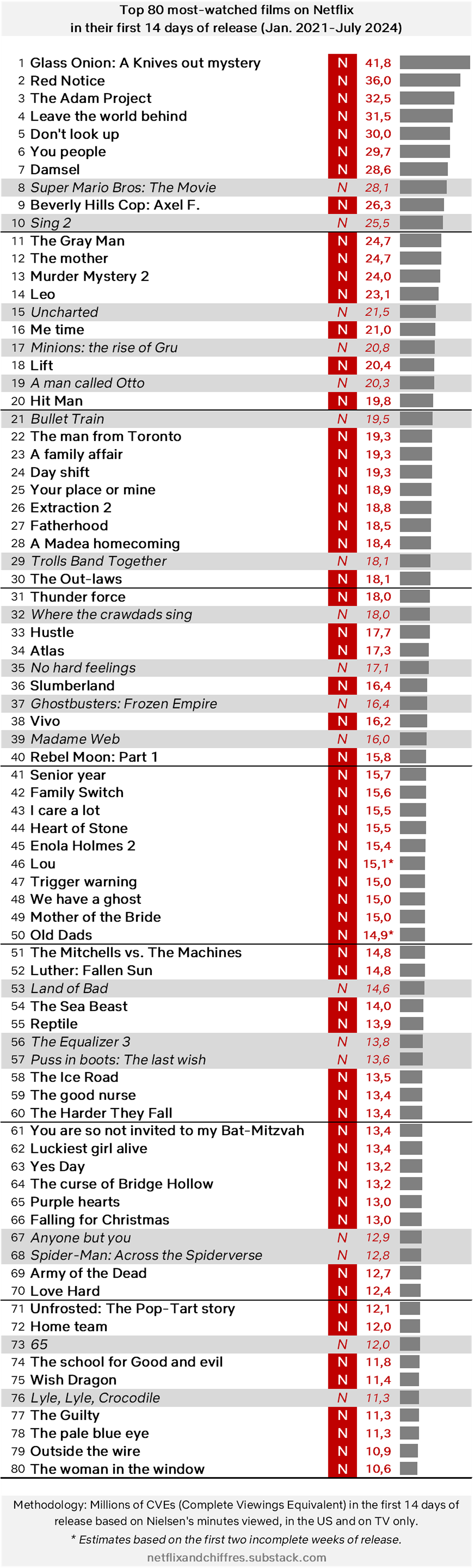

Let’s start by looking more closely at Netflix, the service for which we have the most data on films. Unsurprisingly, streaming original films are everywhere to be seen in the Top 80 most-watched films on Netflix in their first 14 days of release, leaving only 18 spots to theatrical releases.

Once again, Sony films are making up the most of them (12) with Universal animated films being second with 5 films. Land of Bad is the standout, being the only real theatrical film to have managed to break out “organically” on Netflix, being not from a major studio, a big output deal and not from a known IP, which is in that regard quite impressive. That also says something about all those independent theatrical releases that do their streaming debut on Netflix : they usually just stay out of the Nielsen Top 10 with no discernible real audience on streaming.

If we look at the averages for the Top 5, 10, 15 and 20 for both streaming original films and theatrical films, the gap between the two categories is even wider, starting from 39% to 42% as we go down the charts.

The streaming original hits on Netflix are just bigger than the theatrical hits and that can be attributable to several factors : the recommendation algorithm to start with but also the daily Top 10 and the “Coming soon” part of the app that keep subscribers on top of new releases. With that, Netflix usually manages to get its new American original films in front of eyeballs in the US. Sure, some might say that because they release so many movies, some are bound to be hits but it’s not as simple as that as we are talking here, for the most part, about films that are not sequels or part of any cinematic universe or even with a big marketing push from Netflix.

There are flops also on streaming, of course, under the horizon of what Nielsen shows but that’s also the case for theatrical films, even with Sony films, that fail to stay long in the weekly Nielsen charts.

One of the questions surrounding Netflix films is whether they would benefit from a proper theatrical release in U.S. cinemas. One could argue that the most-watched film on Netflix in its first 14 days, Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery, is a theatrical film since it received a limited-time release (one week) but in more U.S. theaters than a traditional limited Netflix release. This seems to support the idea.

However, that was in 2022, and since then, Netflix has not repeated the experience of a somewhat wide theatrical release in the U.S. for several reasons, in my opinion. The first is that I think they realized it doesn’t significantly boost streaming views (its top position was predictable since it’s a sequel to a well-known franchise with an extraordinary cast, released during the holiday season, a time when Americans watch the most TV).

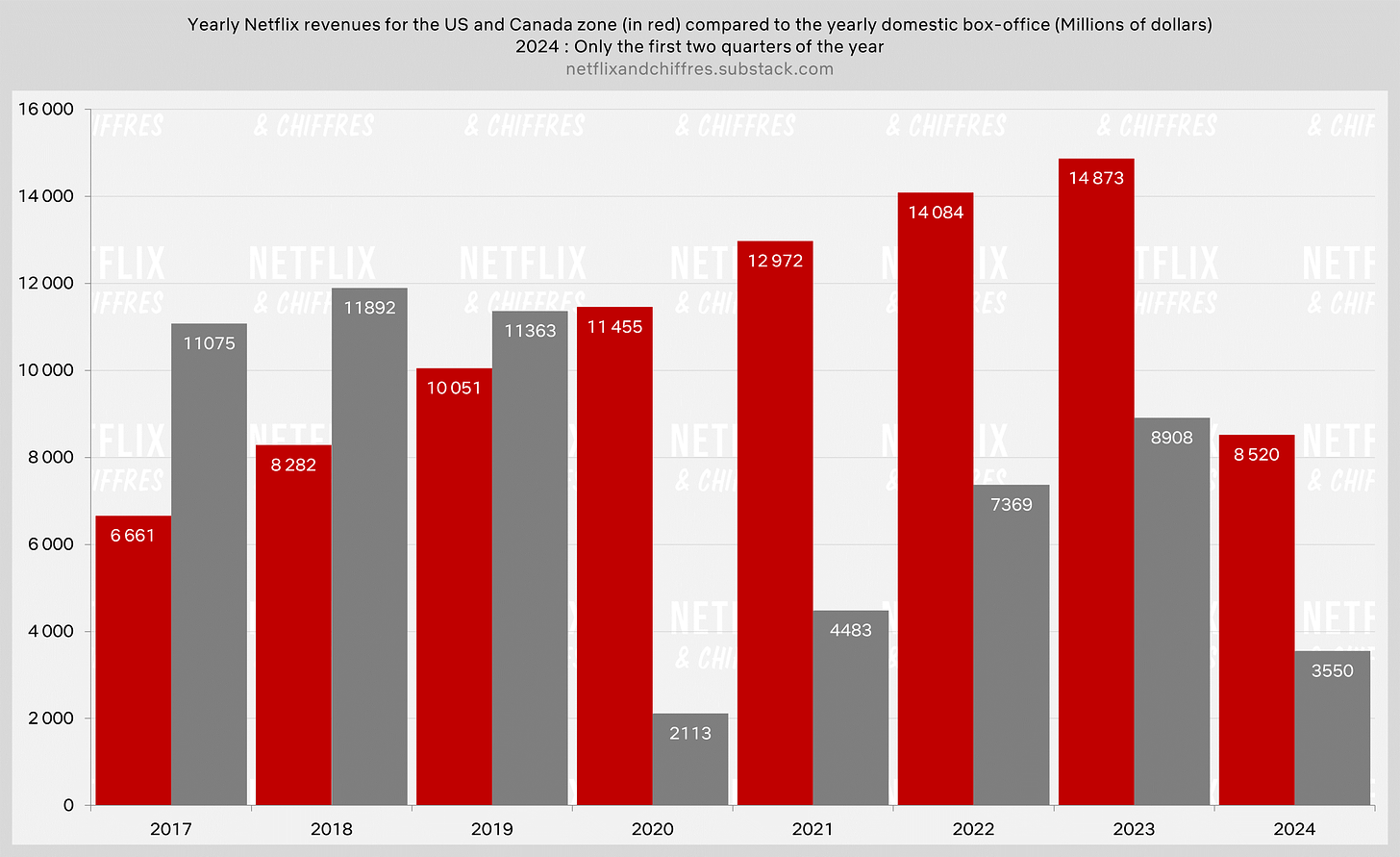

The other reason is that, financially speaking, even a moderately successful wide theatrical domestic release wouldn’t fundamentally change things for Netflix. If we compare the annual U.S. and Canada box office revenues to Netflix’s earnings in the same region, we see that Netflix makes almost double what the entire annual box office generates in U.S. and Canadian theaters.

It should be noted that distributors only keep 40-45% of total box office revenues, sharing the rest with cinema operators. So, in 2024, when Netflix will earn around 16 billion dollars solely from North America, the distributors of all the films released in theaters on the continent this year will share about 3.5 billion dollars.

Now, let's imagine Netflix opts for theatrical releases for its major films. What’s the point for them to spend tens of millions of dollars in the release and promotion of films for a box office success that’s completely unpredictable and, at best, would bring in just a few dozens of millions dollars, a truly negligible amount of revenue compared to what they earn from streaming, all while reducing by 30 to 40% the film's viewership on the service? So far, Netflix seems to be saying there’s no point, and it seems Amazon and Apple are starting to understand this too, but we’ll circle back to that.

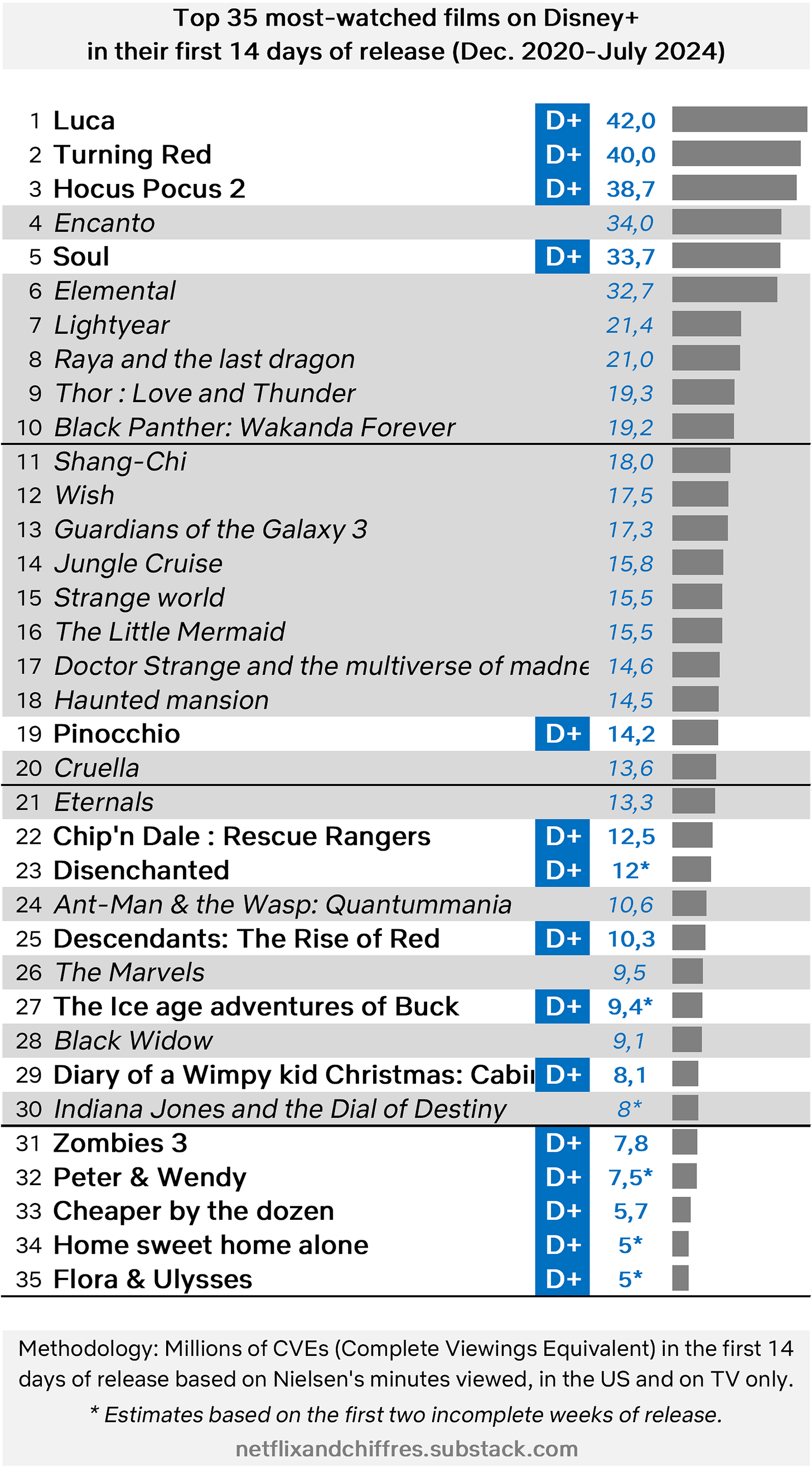

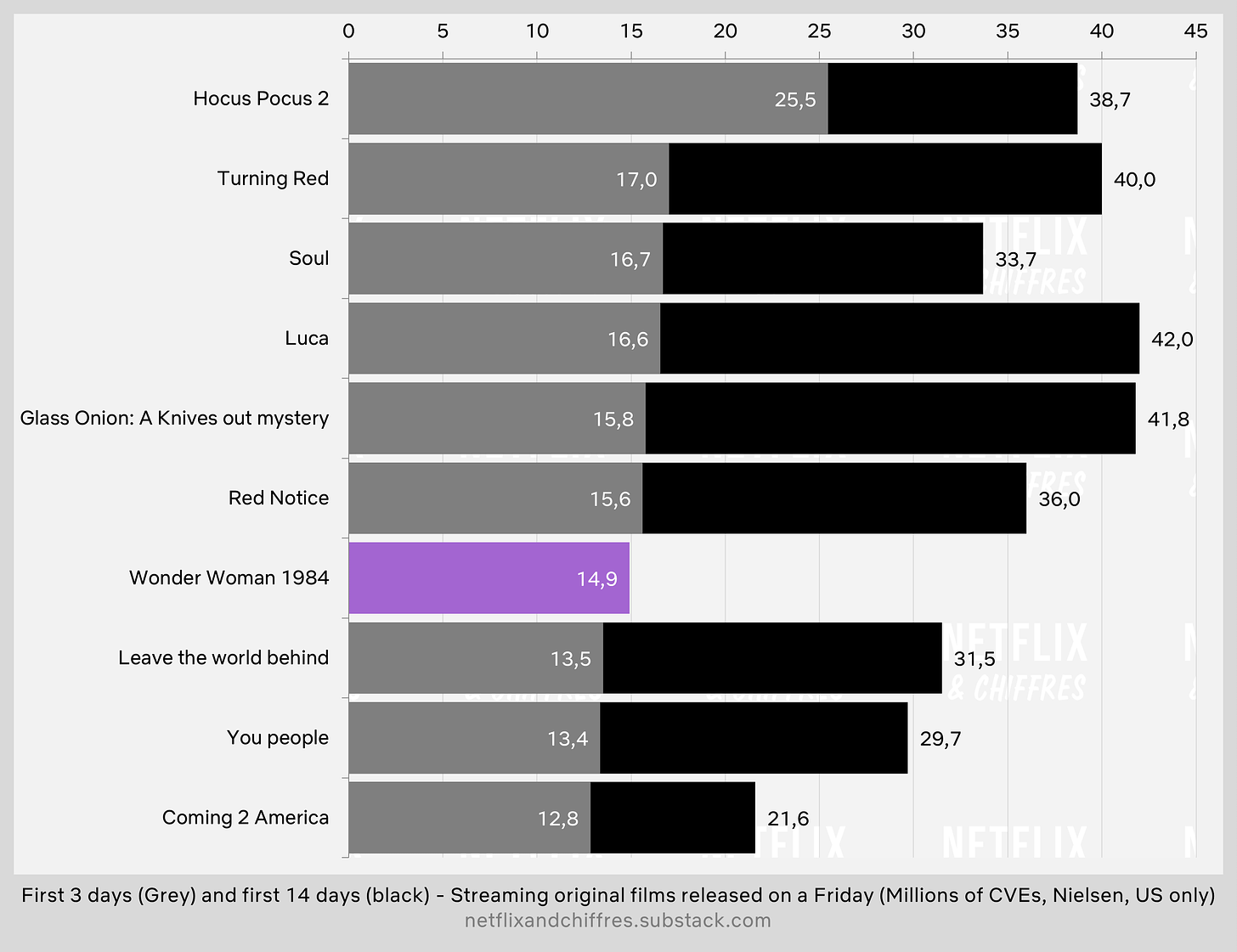

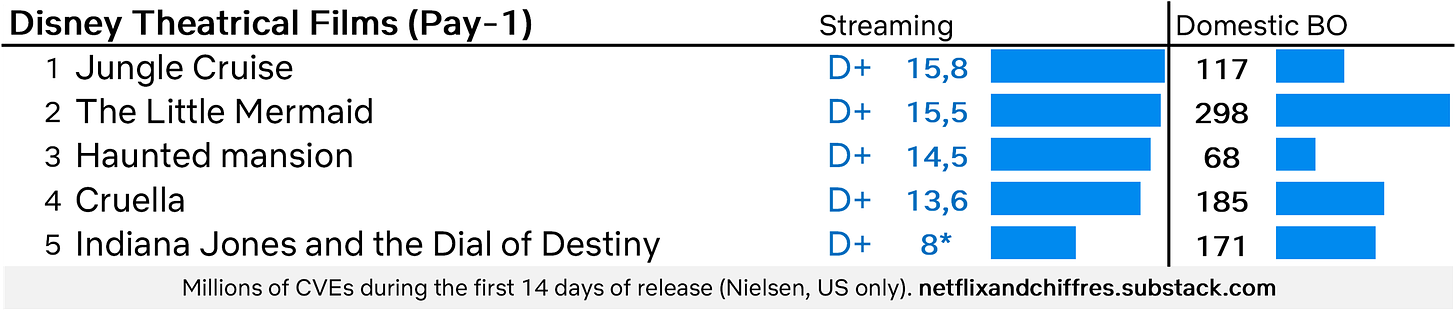

At Disney, however, the interest in theatrical releases seems to have regained strength after the Chapek era, during which, remember, he committed the "crime" of releasing Pixar films directly on streaming with Luca, Turning Red, and Soul. Yet, to Bob Chapek's credit, these films were at least successful on Disney+, as they hold top spots in the Top 35 most-watched films on Disney+ within the first 14 days after their release.

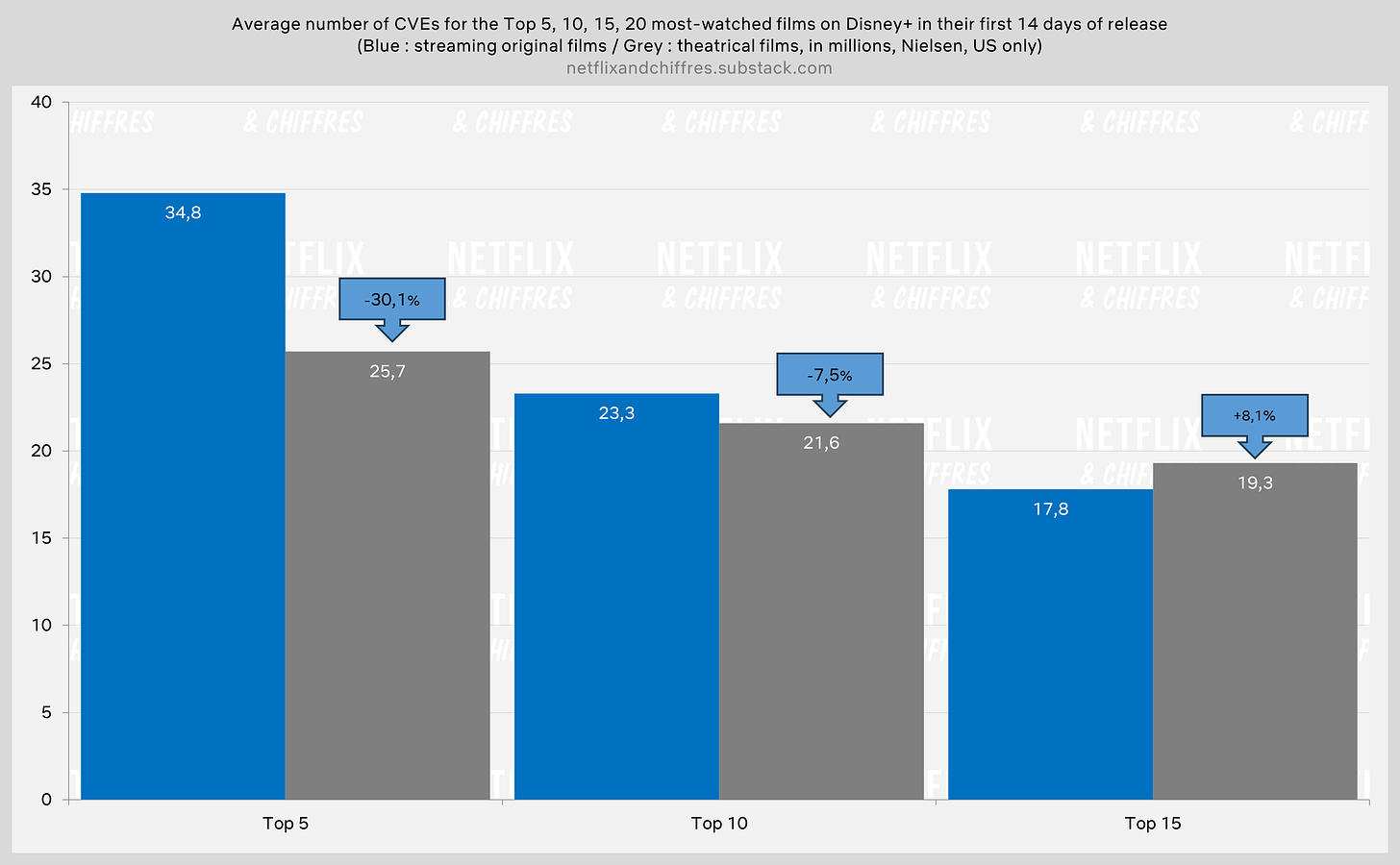

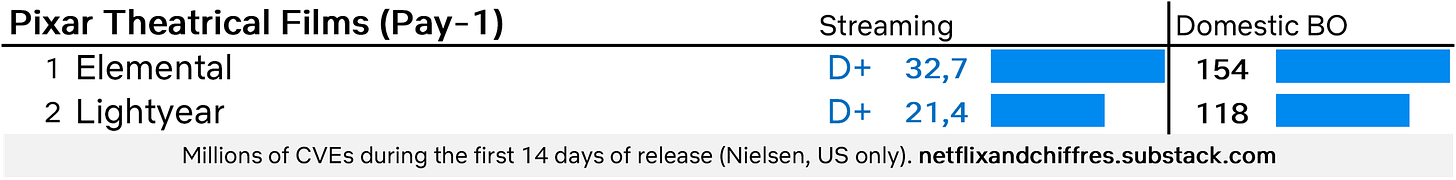

Do you know the percentage difference in viewership between Pixar films released exclusively on Disney+ and those that arrived on Disney+ after a more or less successful theatrical release? I'll tell you: 35%. So here too, we see this "penalty" of about a third in viewership between original streaming films and theatrical films, as we mentioned earlier. However, there's a slight difference unique to Disney+ when we broaden the scope.

From 30% less viewership between the streaming original Top 5 and the theatrical Top 5 on streaming, we jump to an 8% advance for theatrical releases when we broaden the scope to the Top 15, thanks to the slew of Disney/Marvel films that still perform solidly once they hit streaming, while Disney+ original films are inevitably less popular. The real (relative) flop of the Disney+ Original lineup might be Disenchanted, which, with only 12 million CVEs in 14 days, performed far worse than expected, especially after the huge success of Hocus Pocus 2 (38.7 million CVEs in the same period).

However, I probably don’t need to explain that MCU films are more popular with the Disney+ audience than the live-action versions of Pinocchio, Peter & Wendy, or the new versions of Cheaper by the Dozen and Home Sweet Home Alone. This is the strength of the Disney or Marvel brand, which can instantly summon an immediate audience for its releases.

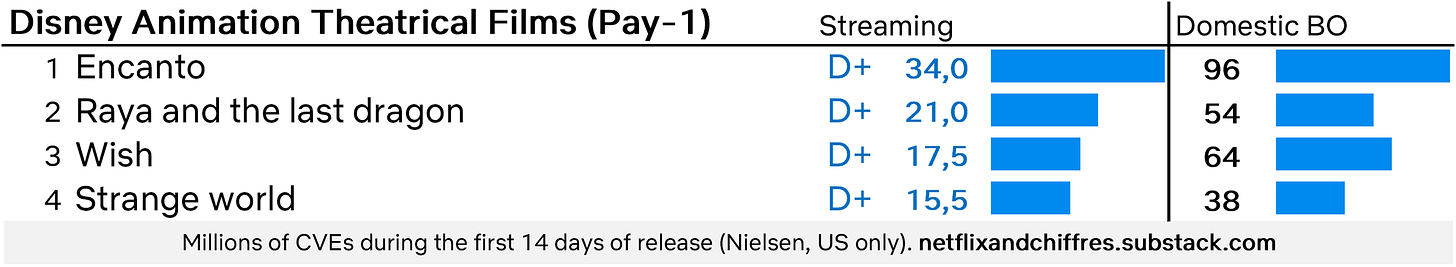

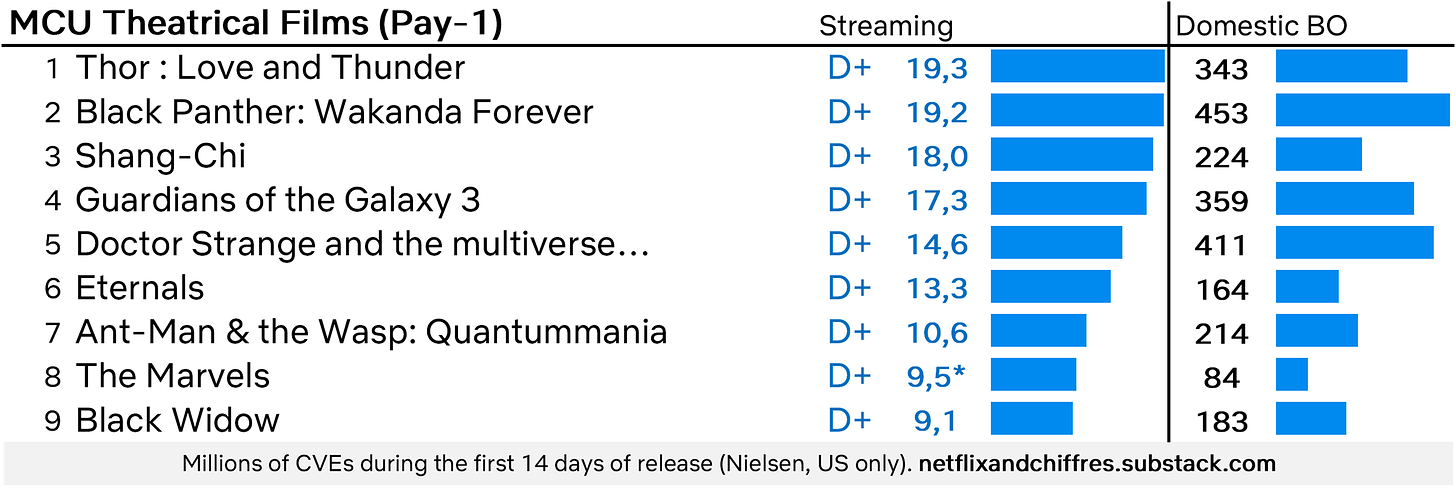

Paradoxically, we could almost use Disney’s case—now firmly rooted in theatrical releases of its films—to finally answer the question of whether original films perform better on streaming than those that have had a theatrical run. We know this is true for Pixar films (though we’ll have to see how Inside Out 2 performs on Disney+ when it comes out in a few days). The Disney Animation films that have performed best on Disney+ are also the ones that vastly underperformed in theaters (Encanto and Raya and the Last Dragon, two theatrical flops for different reasons). As for Marvel, if Disney decided tomorrow to release the next MCU film directly on Disney+, I would confidently predict it would achieve significantly higher streaming numbers in the U.S. than Thor: Love & Thunder and Black Panther 2, the two most-watched MCU films on Disney+ in their first 14 days of release. (let’s say... 35% higher?).

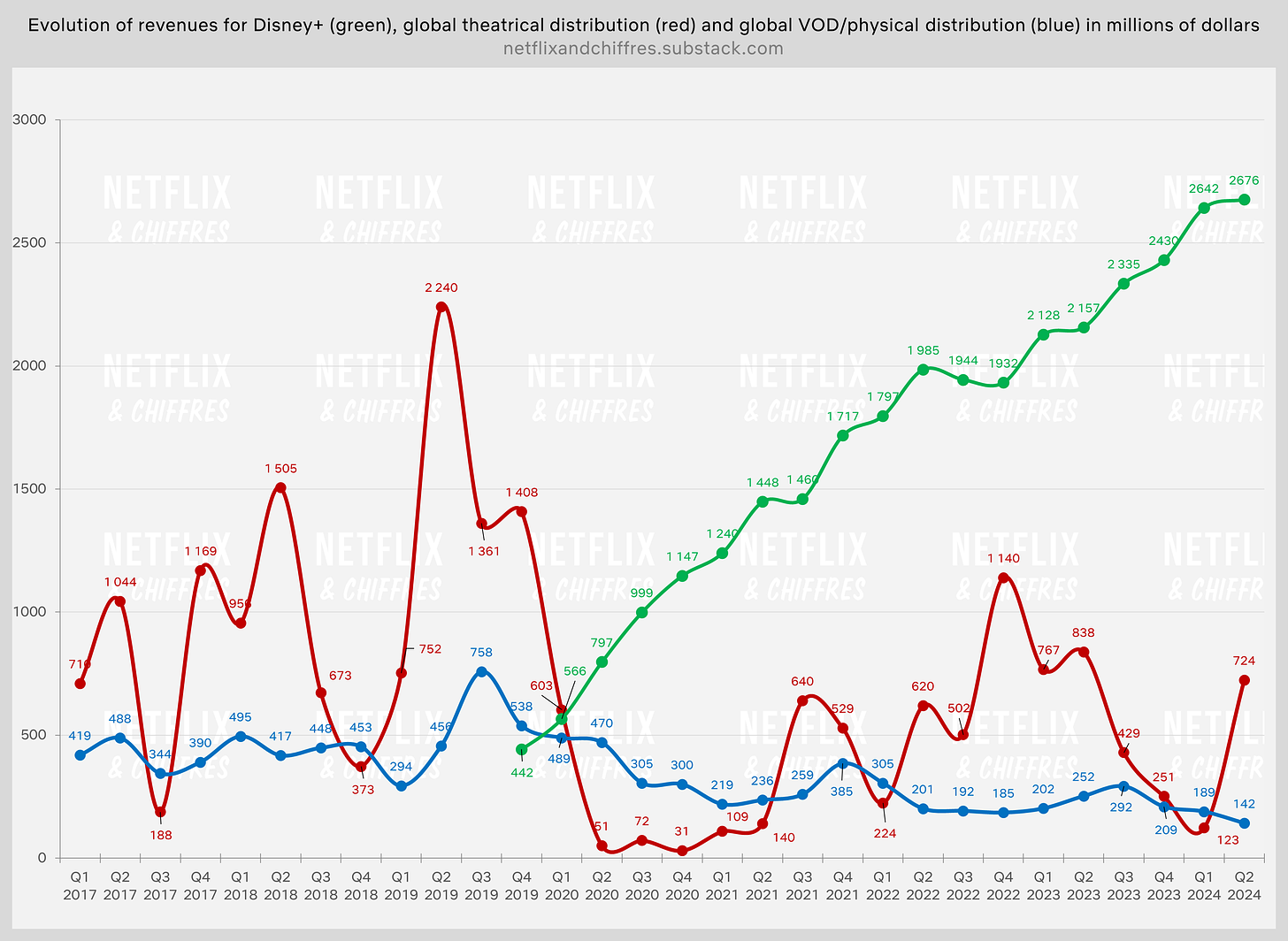

But Disney remains committed to theatrical releases in the U.S. because it's still a company with both hands tied in traditional distribution channels (theaters, physical/VOD, and SVOD), three sectors with very different financial destinies.

Theatrical revenues are unpredictable and rely on hits, something no studio can guarantee (except by trying to rely on sequels, remakes, and reboots—Bob Iger 2.0’s strategy). VOD and physical media revenues have been steadily declining for years (with occasional increases when films perform well in theaters), while Disney+ revenues are rising—not necessarily because the number of subscribers is increasing, but because subscription prices are going up, continuously testing Disney fans' loyalty to the brand.

Chapek decided to sacrifice the red and blue lines a bit in favor of the green line's growth during the COVID era. Meanwhile, Bob Iger seems more focused on bringing the red and blue lines (theatrical and physical/VOD revenues) back to 2019 levels while still increasing the green line (Disney+ revenues) by spending less on original programming for Disney+, especially when it comes to films. It's still a bit early to tell if this strategy will work, though the successes of Inside Out 2 and Deadpool & Wolverine are encouraging signs.

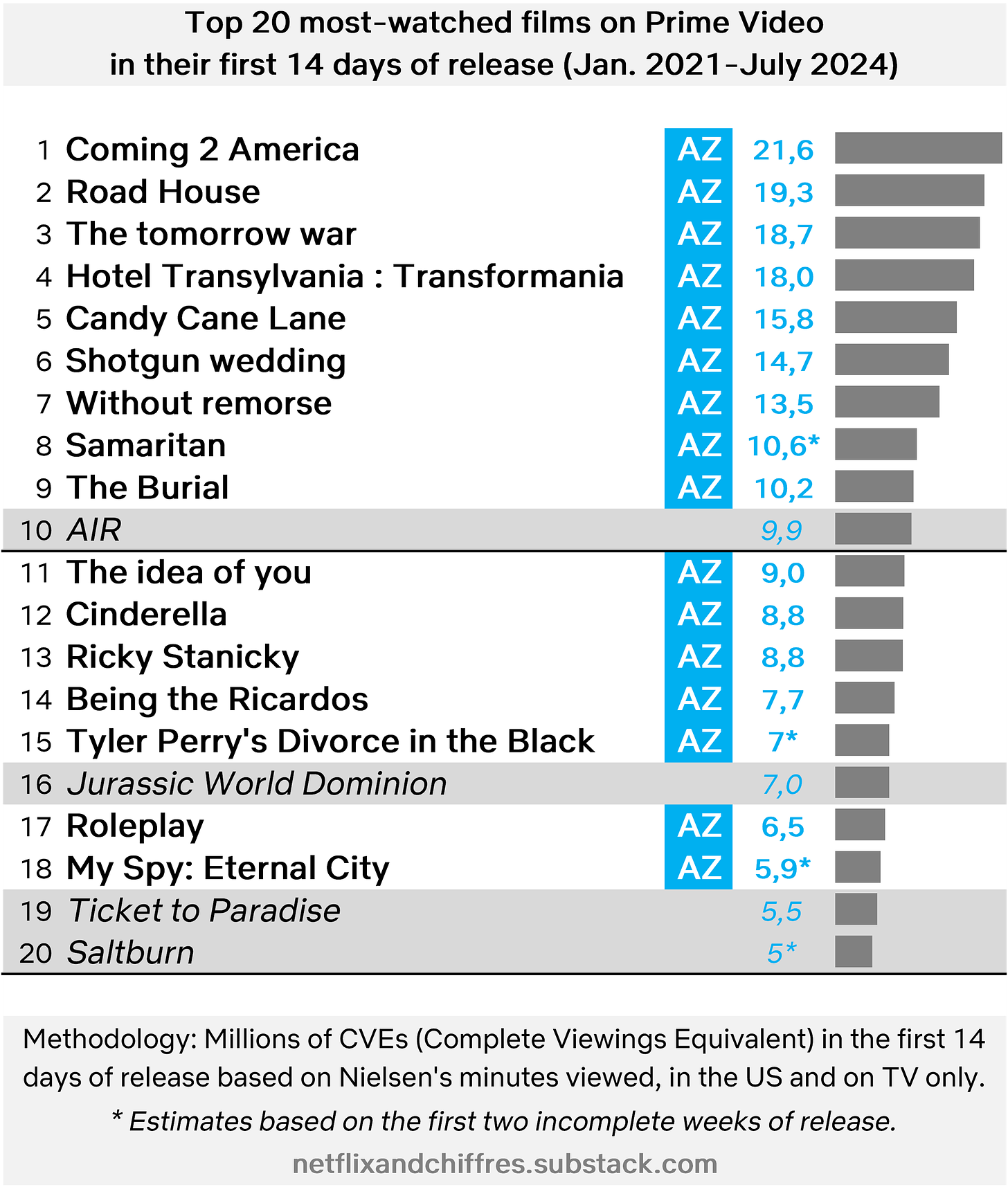

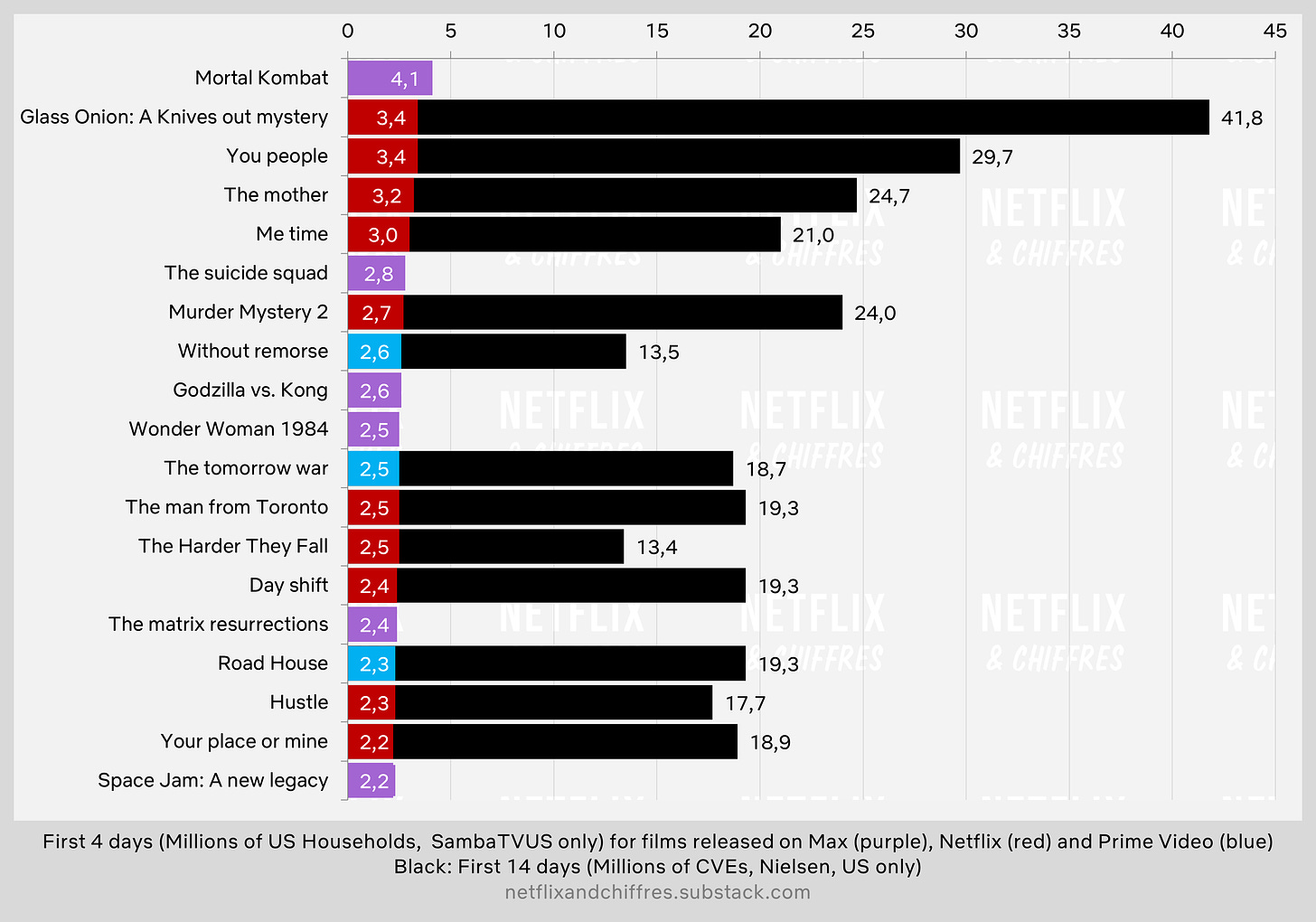

The recent history of Prime Video could be summed up by two press headlines. On one hand, in 2022, “Amazon commits to theatrical distribution in the U.S. and plans to release 12 to 15 films per year.” On the other, in 2024, “Amazon releases the Road House remake directly on Prime, against the wishes of its director.” Indeed, when Road House was released directly on Prime in March 2024, many industry observers wondered why Amazon hadn’t given it a theatrical release. My answer won’t surprise you: the service needed a streaming win, a film it could promote as a global success, which Road House was, with 19.3 million CVEs in its first 14 days in the U.S., making it the second-best film launch on Amazon.

The films released in theaters from this Top 20 are quite varied, with true Amazon releases that created some buzz upon their theatrical release but ultimately didn’t perform well in streaming (like AIR or Saltburn), and Universal films in their second pay window, such as Jurassic World Dominion and Ticket to Paradise. This doesn’t mean that all original Prime films are successes—far from it. It mostly shows that Amazon now chooses to release films in theaters that wouldn’t move the needle in streaming, reserving its bigger and more mainstream films for the streaming platform, such as Road House, The Idea of You, or even Candy Cane Lane, a Christmas movie with Eddie Murphy that could have done well in theaters but which Amazon preferred to keep for Prime.

At Amazon, the difference in viewership between the Top 5 original films and the Top 5 theatrical films is around 70%, about twice the average.

Two tests await for the end of 2024: First is the release of Challengers starring Zendaya in a few days on Prime after its theatrical run and the second test will be the theatrical release of Red One, Amazon’s biggest tentpole film this holiday season and how it will fare on streaming after. Maybe those two tests will reverse the trend—or not.

The other streaming services.

The other streaming services (SVOD) have smaller audiences, but each provides some insights to help answer the question.

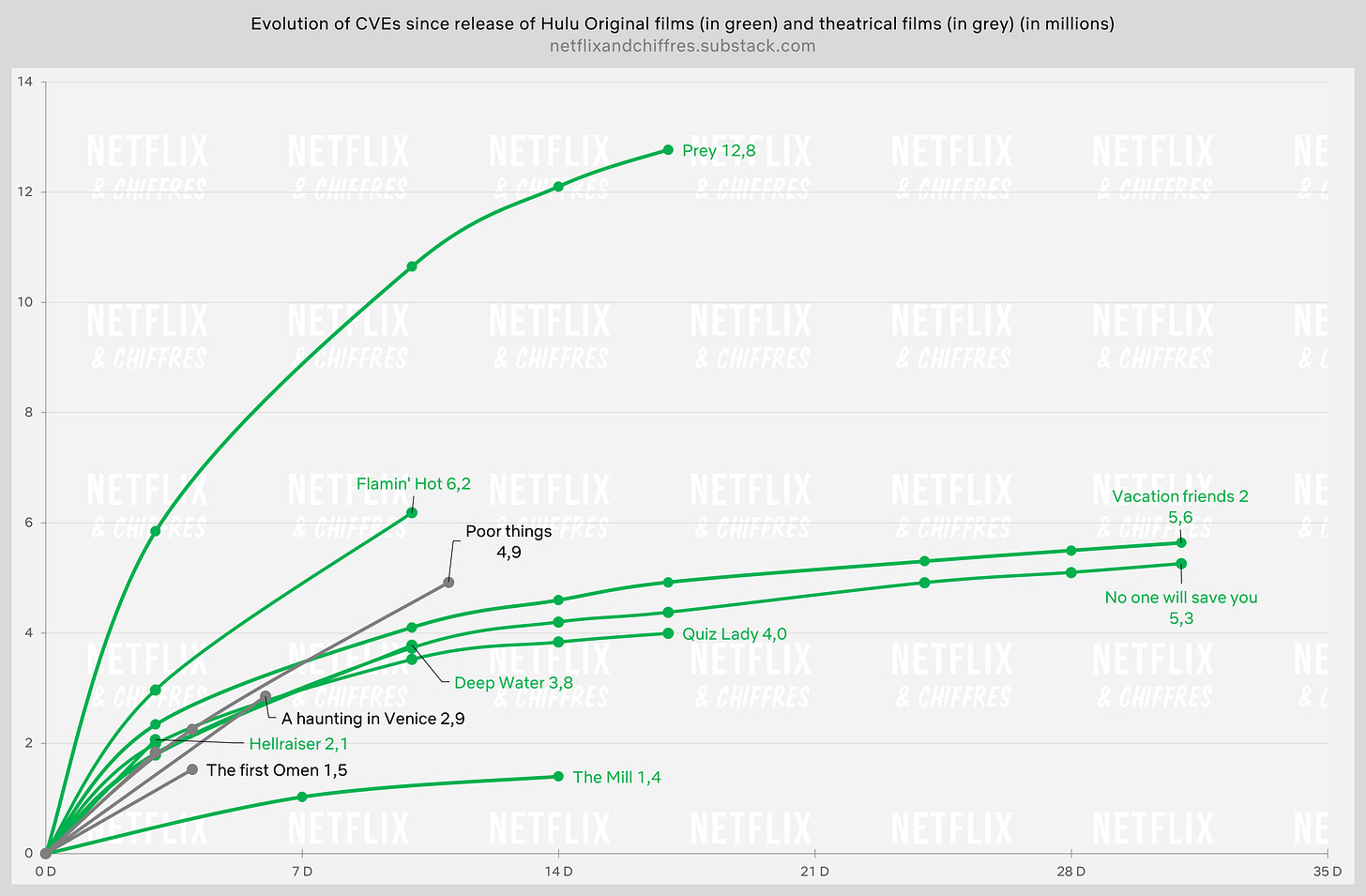

Hulu

On Hulu’s side, the main successes in recent years have been direct-to-streaming films like Prey and Flamin' Hot. Poor Things performed well, but The First Omen and A Haunting in Venice have lower numbers compared to the streaming original hits.

The film I'm most looking forward to, which might provide some additional insights, is Alien: Romulus, a movie that was initially set to be released directly on Hulu (during the Bob Chapek era) in the vein of Prey before shifting to a theatrical release (under the Iger era). Two films from the same universe, one released directly on streaming, the other in theaters... I'm betting on about 30% fewer viewings for Alien: Romulus compared to Prey, though the ability to watch Hulu content on Disney+ now could potentially change things and reduce this gap by giving it a larger audience.

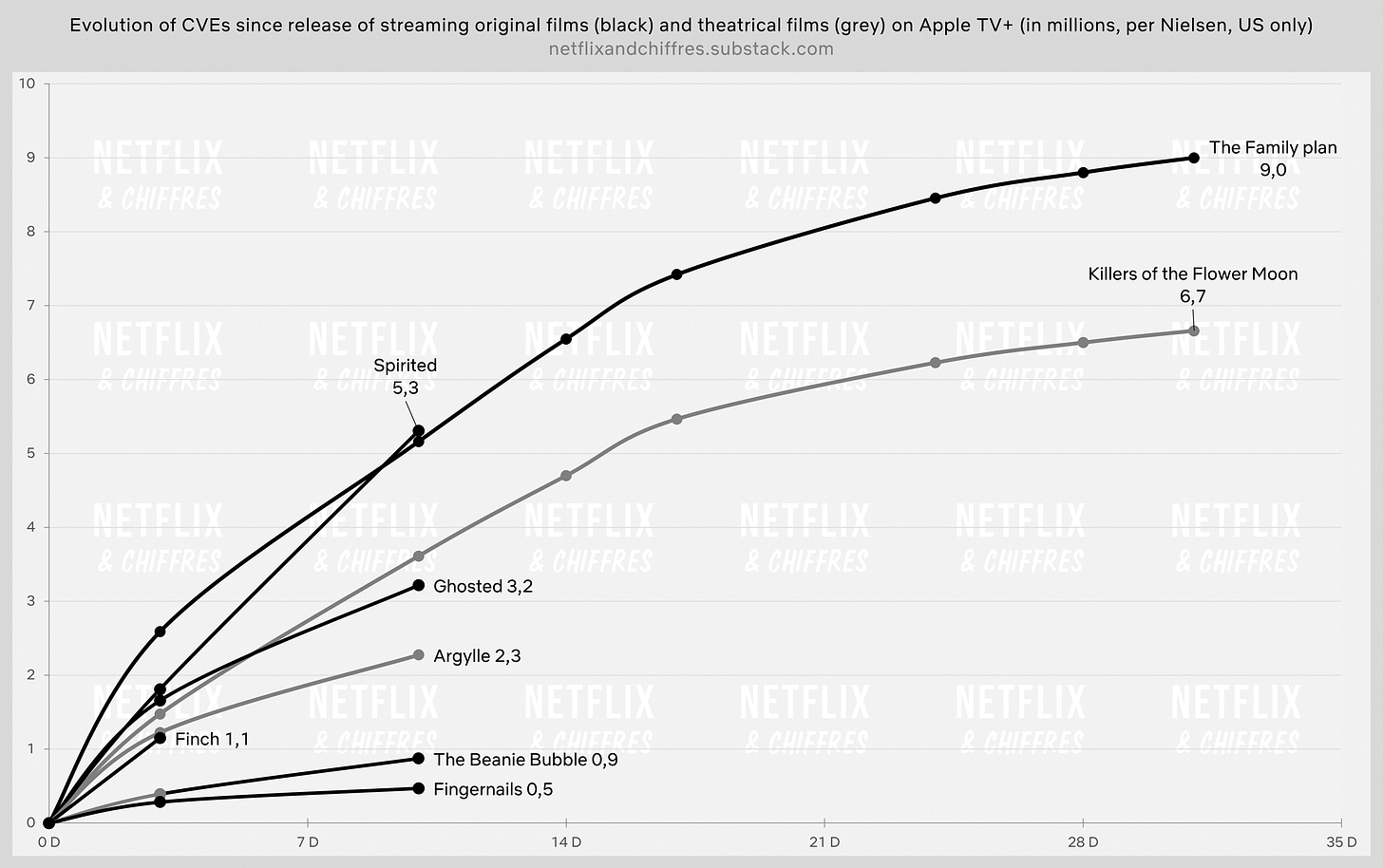

Apple TV+

Apple TV+ is the other streamer that gained confidence and decided to release a few films in theaters in 2023 in an attempt to give these films more prestige, make money, and help them perform better on their platform. Unfortunately, the results haven't quite lived up to expectations, as The Family Plan and Spirited (both originals) likely did better on the service than Killers of the Flower Moon (which had a theatrical release).

We can also mention that Argylle, a major theatrical flop for Apple, didn’t perform well in streaming either, with its numbers coming from leaks since the film never made it into the Nielsen Top 10. Additionally, we have no data at all for the release of Napoleon on Apple TV+ in the U.S. in March 2024, another one of Apple's theatrical bets. Apple invested $700 million in these three films, with only $430 million in global box office revenue (after deducting cinema operators' shares, partner studios, marketing, and release costs, Apple likely only pocketed around $50 million), unflattering headlines about Apple’s visible flops and almost zero impact on streaming viewership.

The consequences came quickly: Apple has apparently decided to release far fewer films in theaters, starting with Wolfs, featuring George Clooney and Brad Pitt, which will now premiere directly on Apple TV+ at the end of September. Perhaps it could break into the Nielsen Top 10, though Apple TV+’s latest original film, The Instigators with Matt Damon and Casey Affleck, failed to do so despite its exclusivity on the service. The problem for Apple TV+ may lie elsewhere.

Max

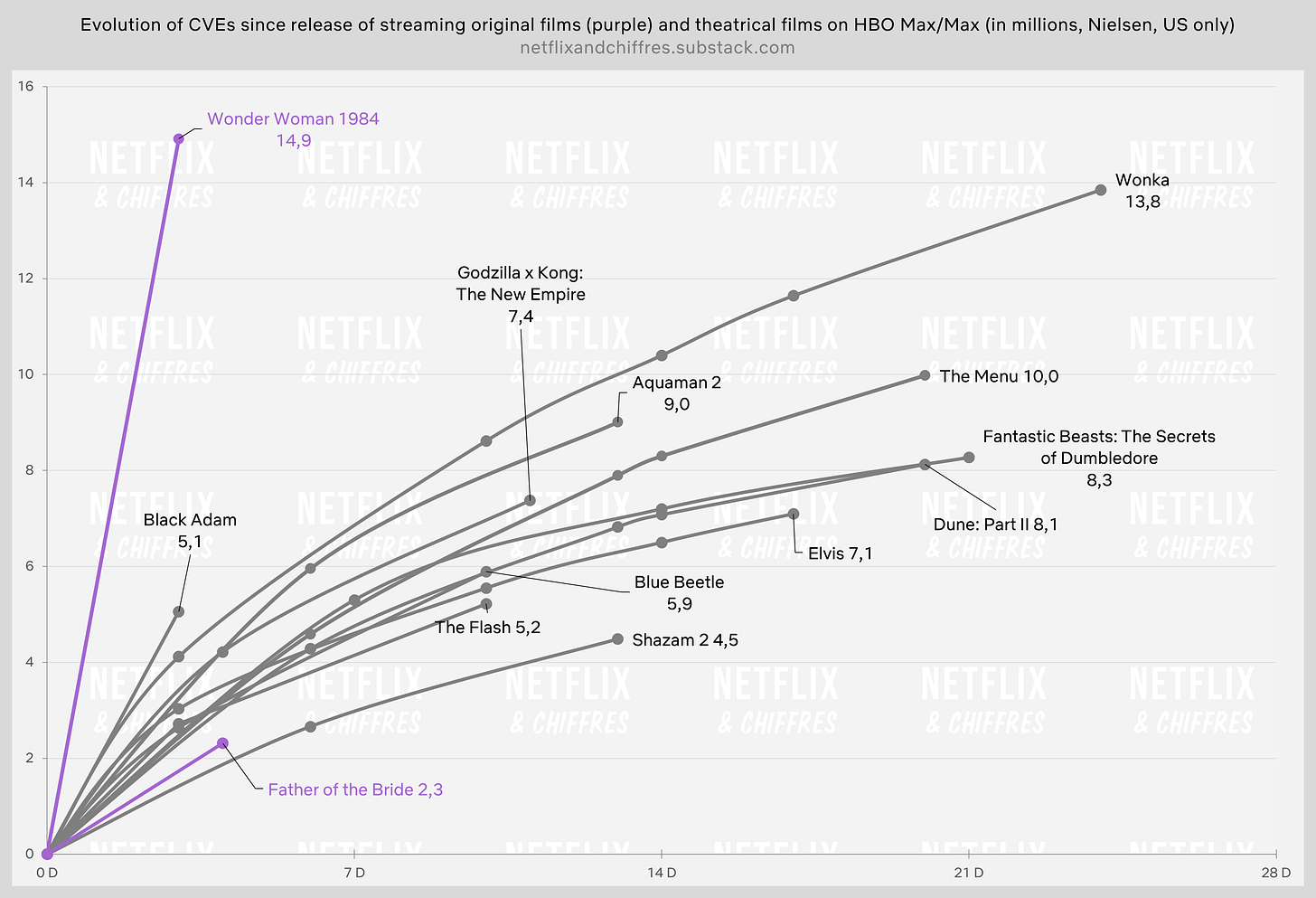

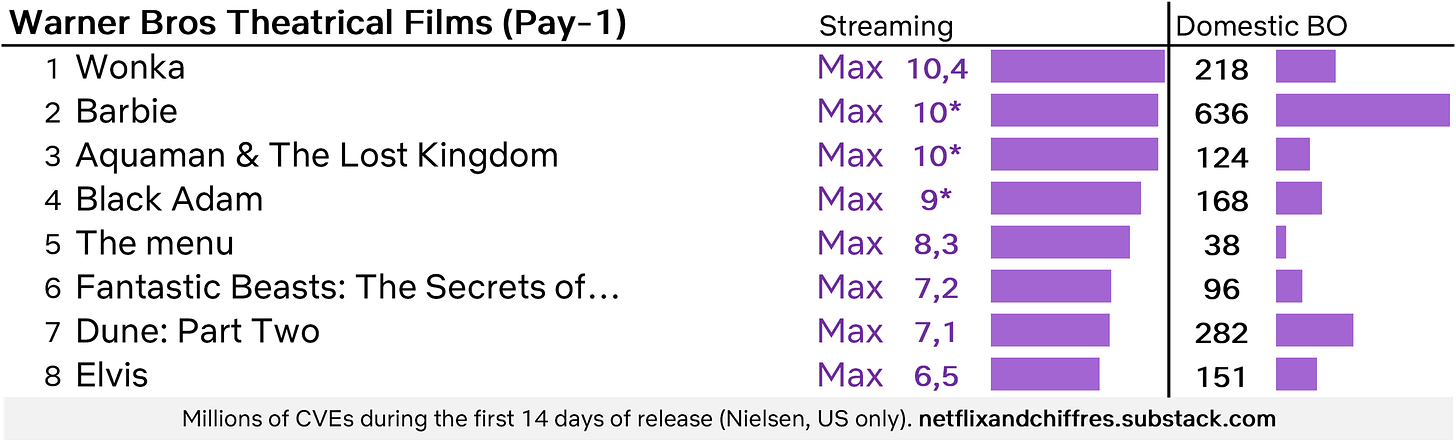

In this chart of major releases on Max, I didn’t include Avatar 2 and Free Guy since they were released simultaneously on Max and another service (Hulu and Disney+ respectively), without any clear breakdown of viewership for each platform. However, I did include the two direct-to-streaming films for which we have Nielsen data: Wonder Woman 1984 (an exceptional gift from Nielsen, as they weren’t reporting on HBO Max at the time) and Father of the Bride, a very generic rom-com that managed to stay in the Nielsen top rankings for just one week.

The case of Wonder Woman 1984 is really interesting because it marks the start of Project Popcorn, WarnerMedia's decision to release all its 2021 films simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max, as the service was called then. However, from this entire lineup (which included Dune, Matrix 4, Godzilla vs. Kong, etc.), we have no Nielsen data, as they weren’t officially tracking HBO Max at the time. The only number we have is for the first three days of Wonder Woman 1984, and as you can see, those numbers are much larger than any of the other theatrical releases on the service since.

Granted, it was a unique period—Christmas 2020—but still. It’s entirely possible that all the films from Project Popcorn in 2021 had much higher viewership than all those I ranked earlier in my article, and we just don’t know because they fall into Nielsen’s blind spot. For Wonder Woman 1984, the film likely would have ranked high after 14 days, potentially with over 30 million CVEs.

And Wonder Woman 1984 isn’t the only film in this situation. If we look at the data from SambaTV, which provided viewership measurements for the films from Project Popcorn, it’s entirely possible that if Nielsen had shared streaming viewership numbers for Mortal Kombat, The Suicide Squad, Godzilla vs. Kong, The Matrix Resurrections, and Space Jam: A New Legacy, these films could have easily surpassed 14 million EVCs (equivalent viewership counts) within 14 days, according to Nielsen. That would make them record-breaking titles for Max.

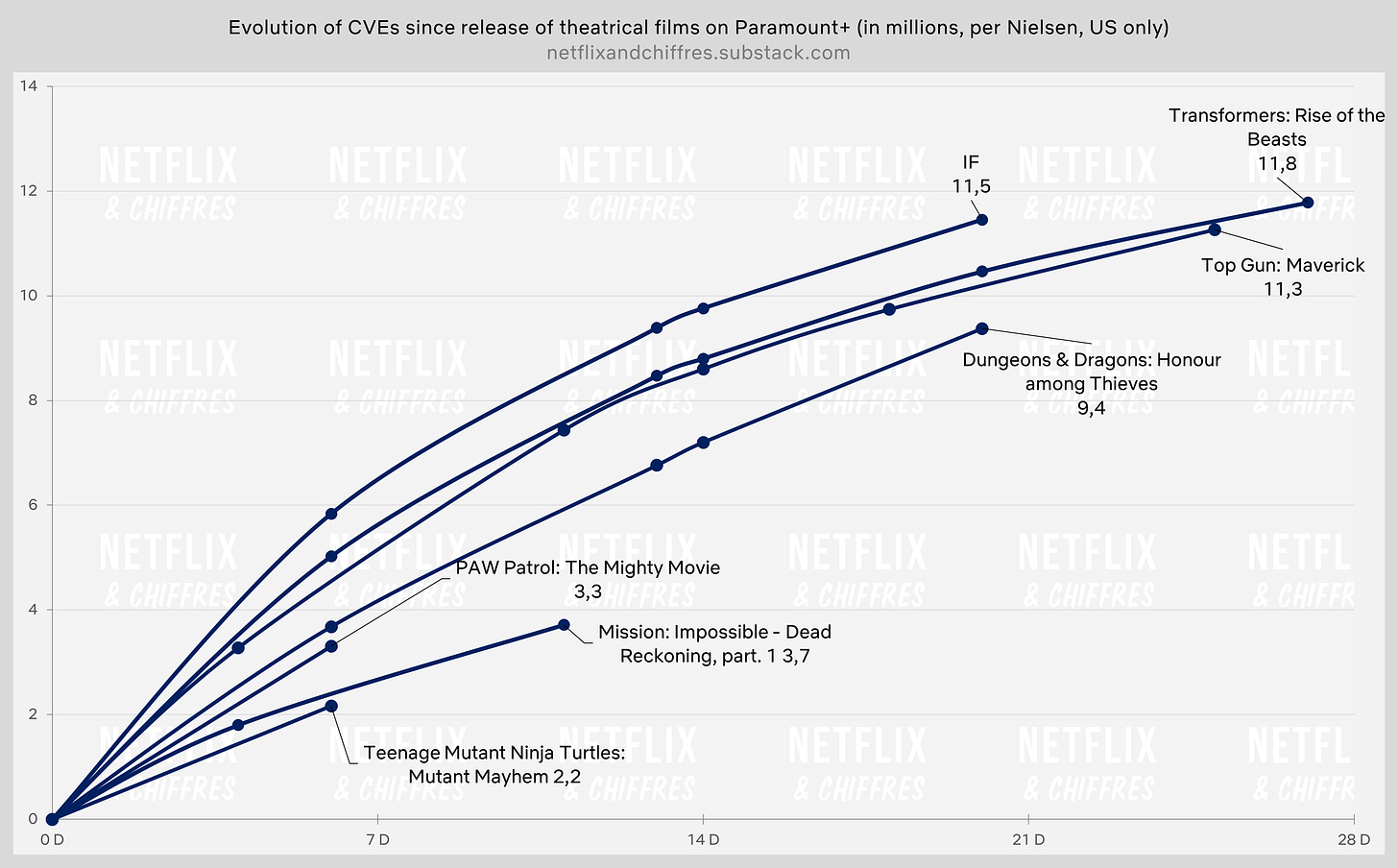

Paramount+

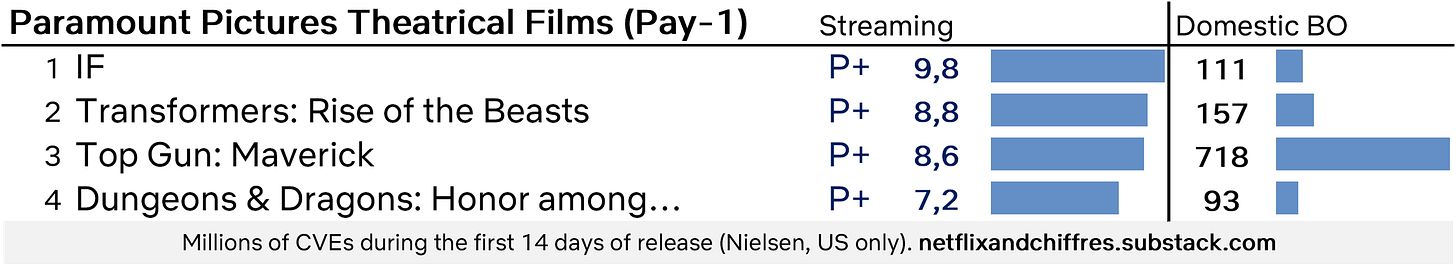

In my dataset, Paramount+ only managed to break into the Nielsen Top 10 with its theatrical films. However, the rankings are quite distant from their box office achievements, with IF performing better than Transformers: Rise of the Beasts and Top Gun: Maverick.

It's also worth noting that Paramount+ hasn’t released many original films, and it’s one of the later services added by Nielsen. However, some of its originals, like Good Burger 2 and Finestkind with Jenna Ortega, could have performed on Nielsen but they were no-shows.

As Paramount+ is in the process of being acquired by Skydance, it will be interesting to see whether it will start releasing “big” films directly on streaming or if it will continue as the primary pay-one window for Paramount’s films.

Peacock

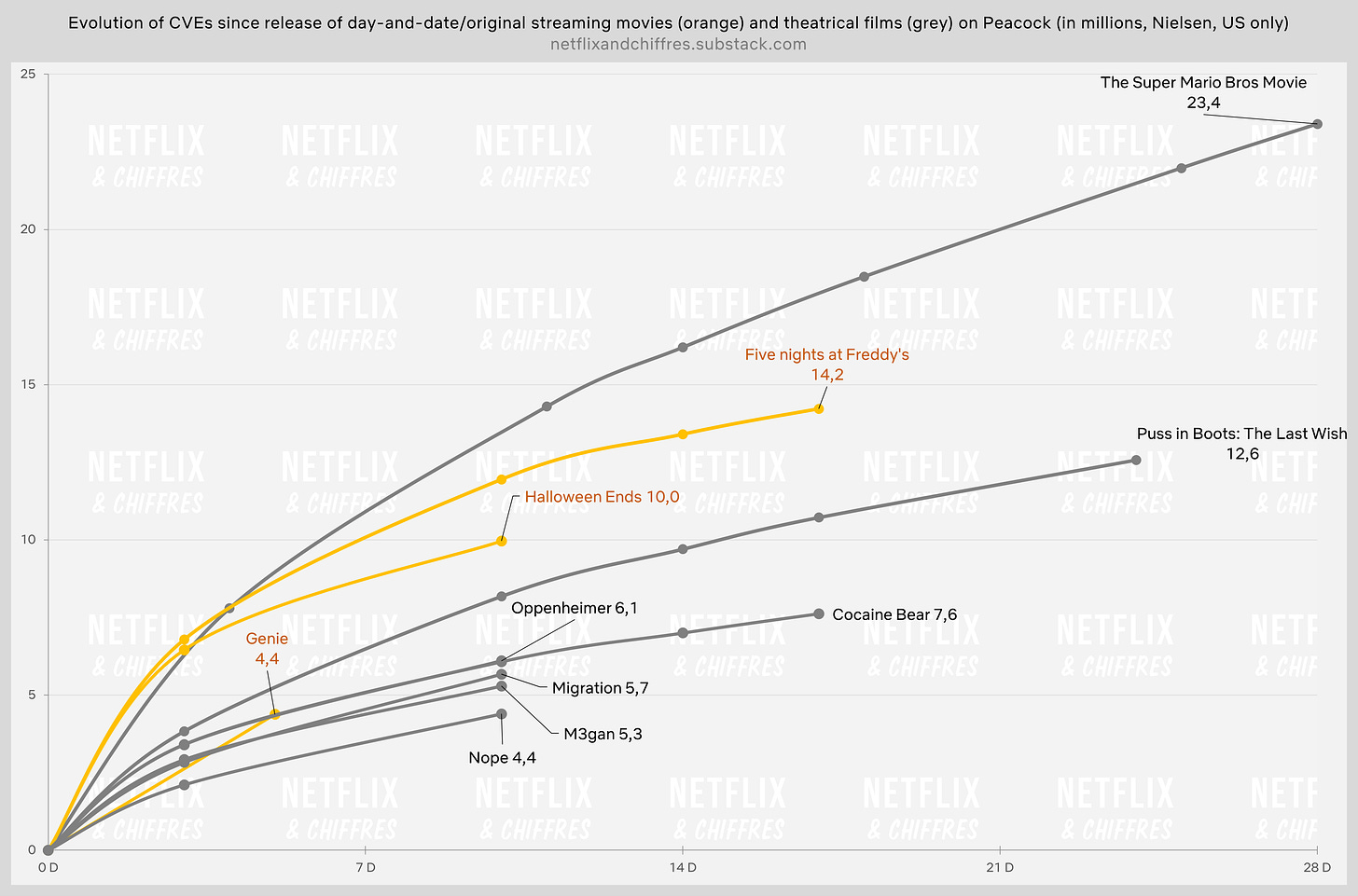

Finally, let’s look at Peacock, which has a distinctly different strategy compared to the others. The Universal/Comcast service opts for simultaneous releases in theaters and on Peacock for some films, and it seems to be working!

Aside from the outlier The Super Mario Bros. Movie, the two most-watched films during the launch period on Peacock are Five Nights at Freddy’s and Halloween Ends, both of which were released simultaneously in theaters and on streaming. They are also considered box office successes, which suggests there’s no cannibalization between the two release modes.

The only Peacock original film in my dataset, Genie with Melissa McCarthy, had a promising start but quickly dropped out of the Top 10, making it hard to assess its long-term performance. Nonetheless, it appears to be performing better than Oppenheimer and Cocaine Bear, which had similar early viewership patterns. This underscores that box office performance doesn't always directly translate to streaming success.

Are box-office successes automatically streaming successes?

To determine if there is a correlation between box office success and streaming success, I set up the rankings of the 56 most-watched theatrical films on streaming between January 2021 and July 2024 along with their North American box office earnings. Here it goes:

On paper, it’s challenging to identify a clear correlation between box office success and streaming performance, with a mix of hits and flops across the top rankings. However, when we reorganize these results by focusing on major film categories and the services on which they were released, a different picture emerges.

Let’s start with Disney Animation films released in theaters. To be clear, all four films are considered flops at the box office, but their streaming viewership on Disney+ aligns with their performance order.

Released as theaters were slowly reopening, it’s plausible that Raya and the Last Dragon might have performed better in a more favorable context. We've already discussed Pixar films, which also follow the order of North American box office performance, although not always with the same magnitude.

On the MCU side, things are a bit more mixed. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness have performed comparatively worse on Disney+ than they did in theaters.

One thing is clear: very few people were interested in The Marvels, both in theaters and on Disney+. The film struggles to outperform Black Widow in its “free” Disney+ release (the film was released on Disney+ Access, meaning it was available simultaneously in theaters and as a paid option on Disney+ before being accessible to all subscribers, and these are the numbers I used).

Ending with Disney’s other films that don’t fit into the previous categories, Haunted Mansion performed better on streaming than in theaters, while Jungle Cruise likely would have fared better in U.S. theaters under more favorable release conditions (i.e., not during the COVID-19 pandemic). For the rest, the order of performance is relatively consistent.

In the Sony-Netflix deal, I find it quite interesting that Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, which had the best box office performance among the Sony films, didn’t achieve the highest viewership on Netflix. My hypothesis is that “adult” animation might perform less well on Netflix compared to live-action films or children's animation, although Lyle, Lyle Crocodile didn’t necessarily perform better on Netflix either.

Tom Hanks’ star power is evident in streaming, with A Man Called Otto coming in second place behind Uncharted, which is the most-watched Sony live-action film in both theaters and on streaming among the Sony-Netflix deal films.

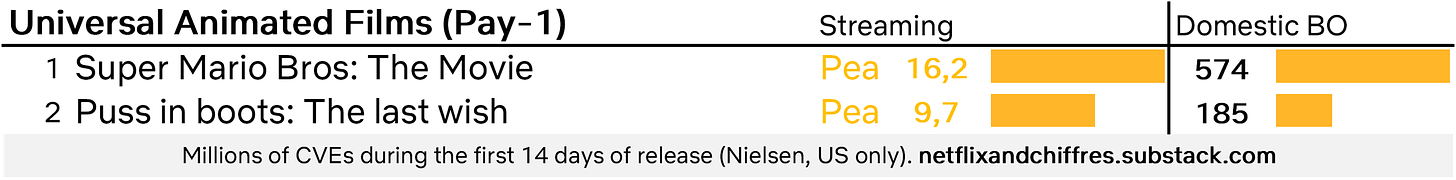

When it comes to Universal Animation films arriving in their second window on Netflix, the order of performance is nearly consistent, though Sing 2 might be an exception.

For films that had simultaneous releases on two services (Max and a Disney-owned service), Avatar 2 performed better than Free Guy on streaming, but not necessarily by the same margin as their box office difference.

Staying with Max, there doesn’t seem to be an intrinsic coherence between streaming and box office performances. Barbie, which was a massive theatrical hit, had a peculiar trajectory on Nielsen, appearing in the Top 10 only in its 1st, 3rd, and 5th weeks. This led me to estimate its viewership at 14 days, but even then, it doesn’t seem to have set any viewership records.

It’s worth questioning whether there’s a “saturation” effect for live-action films following a massive box office success. The fact that Barbie only ranked 42nd in the general top and that on Paramount+, Top Gun: Maverick—a major hit from 2022—is outperformed by IF and Transformers: Rise of the Beasts might suggest that a huge theatrical success can diminish a film’s impact once it reaches streaming. This could be because the film has already been seen by a large audience weeks or months earlier and that this audience is not particularly keen on watching it again when it hits streaming a few months later.

The Super Mario Bros. Movie is an exception to this trend, as it managed to be a blockbuster both in theaters and on streaming. It performed exceptionally well during its theatrical run and continued to succeed in its streaming windows on both Peacock and Netflix.

Finally, let’s take a look at the streaming performances of the 100 highest-grossing films at the U.S. box office from 2021 to July 2024. This overview highlights that while we have a lot of audience data, there are still many gaps and things we don’t know. For instance, Spider-Man: No Way Home, the highest-grossing film over the past three years and a half in the US, was released on Starz and we have no available audience data on streaming for it.

For nearly a third of the films in this Top 100, we lack visibility into their streaming performance. This is either because they were released on services not tracked by Nielsen or because they were released before Nielsen officially began tracking them. Despite these gaps, we can still draw some conclusions based on the available data.

Conclusion

What can be taken away from this lengthy study and the data revealed here? A few points seem important to me.

Films released directly on streaming platforms generally perform much better than films that were first released in theaters. Whether on Netflix, Disney+, Hulu, Amazon Prime, Apple TV+, or potentially Max, all the most-watched films during their launch period are those released directly on streaming. The most-watched films released directly on streaming are 30 to 40% more watched than the most-watched films released in theaters but watched on streaming. And it feels logical, don’t you think?

“Content is king, but distribution is queen”. This adage holds true here as well, since we see that the viewing numbers for a film that premieres on Netflix are not quite the same as those for a film that premieres on Hulu. Netflix is, in fact, the only service on which theatrical films achieve more viewings in their second window than in their first window, as seen with Universal’s animated films, which get more views on Netflix than on Peacock. Meanwhile, Universal’s live-action films get more views on Peacock than on Amazon Prime in their second window. There is therefore also a premium attached to the distribution platform. Users stick to their preferred service and watch what is available on it. They don’t automatically switch to other services just because films are released there. We can also question whether the conclusions of this analysis would be somewhat different if, for example, the biggest box office hits were released first on Netflix. Only 12 of the top 100 box office hits of the last three years have premiered on Netflix first, with only 4 of the top 50 (and, of these 4, only 2 had released by the time I wrote this). Having films that have performed well at the box office is good, but pairing them with a platform that has strong engagement from its subscribers is even better. Would they reach the levels of viewings of the biggest straight-to-streaming films? Probably not but that’s a question worth asking and let’s hope Sony manages to release a record-breaking theatrical film soon so that we can answer that question more decisevely.

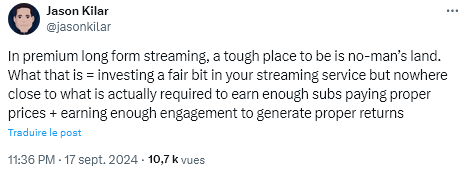

Original films drive more engagement and are therefore an important aspect of a streaming strategy, even if hard to quantify. If original films on streaming platforms are watched more, they generate more engagement on the platform from subscribers. Therefore, focusing a part of a streaming service's strategy on exclusive original films (or simultaneous theatrical/SVOD releases) seems essential, and this was the whole thesis of Jason Kilar, former CEO of WarnerMedia and the originator of the Project PopCorn before being ousted due to the merger with Discovery. To succeed in streaming, his theory is that it is necessary to invest heavily in programming to acquire subscribers and gain engagement to generate massive revenue, and exclusive films are a part of this equation. This massive investment in content was evident in 2021 with Disney under Bob Chapek and WarnerMedia under Jason Kilar, with quite significant results as the subscriber growth of both services at the time was quite strong. Then, in June 2022, the major Netflix Correction took place, halting this investment. Chapek was ousted, Kilar as well, and Disney+ and Max found themselves in the no-man's land described by Jason Kilar: investing a bit in content but not at a level of spending (and boldness) necessary to generate significant long-term profits, enough to outshine any potential gains from a theatrical release. Only one streaming service has relatively stayed the course, and that is Netflix with admitedly great results, two years in.

In this analysis, I did not try to tackle the “popularity” or “impact on culture” aspect because all the web-based “demand” indicators (Wikipedia pages traffic, Reelgood or JustWatch charts, IMDb ratings,…) feel a bit disconnected to what people are actually watching. For instance, The Star Wars show The Acolyte was canceled on Disney+ even though it was the number #1 show per Reelgood for several weeks. The most-watched series on broadcast last season with 10 million US viewers on average, Tracker on CBS, only ranks #247 on the most popular series of the year chart on TelevisionStats which aggregates “online demand” indicators. So I don’t feel like there are relevant web indicators to really quantify what people watch and its impact but that’s another topic for another day.

I hope you liked this analysis and if you did, feel free to subscribe to my newsletter. The texts are in French but the graphs are in English.

If you have any questions about the data, the methodology and the findings, please feel free to reply (if you got it by mail) comment or reach out to me on X @filmsdelover.